Introduction

Recent years have seen an increasing focus in government and local authority policymaking on the centrality of place and ‘place-based’ policy. This is illustrated, by the Scottish Government’s adoption of the ‘Place Principle’ to guide its policymaking and to drive public service reform which I referred to in my previous post. The objective of place-based policymaking is not only to aid the development of vibrant successful places in themselves, but also recognizes that it is through places that wider objectives for economic development, sustainable development and social wellbeing will be achieved.

This centrality of place in policymaking raises important questions about how place is understood by public agencies and the extent to which any such understandings are shared between public agencies and by those living and working in place communities. Such understandings are key to how agencies operationalize the concept of place in pursuit of their place objectives, and in turn to how they assess the impact and outcomes from actions for the achievement of their policy objectives. This paper explores the basis on which stakeholders in these processes can judge what is a ‘good place’ and gauge how much progress has been made to achieving such an outcome.

A discussion of the quality of a place is essentially concerned with the relationship between people and their place environment. There are different theoretical approaches in the literature to understanding the people-environment relationship. Vidal et. al. (2010) summarize these in 3 central themes: first, places and the process of meaning creation, second identity processes and the relationship with place, and third the bonds or place attachment which people establish with places. Here we concentrate on the first of these and follow Relph (1976) to see place as the outcome of interaction between the physical form of a space, its functionality (activities occurring in a place) and the psychological (emotions, cognitions and meanings associated with a place. He uses the term ‘placeness’ as an overarching term which refers to a state or condition of place which embraces the diverse qualities, interpretations, uses and experience of place. Placeness has various other definitions: for the purposes of this paper the term will be understood to refer to the ‘quality of being a place’.

Public authorities, planners, developers, employers and residents all have an interest in place quality and the indicators which characterize ‘place’ for them. Policies aiming to build quality places require a multi-faceted approach. They need to seek not only to influence the physical features and layout of a space but also to capitalize on a local community’s assets, inspiration and potential, with the intention of creating places which promote people’s health, happiness and wellbeing, economic security and aspirations for their place and for their community as a whole. Clearly a large range of factors and policy actions will be relevant to the achievement of a place which successfully meets these needs and aspirations.

There is a growing evidence base for linking features of place design with benefits derived by those who live in a place. The evidence base indicates that quality design brings added value with respect to health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. The evidence base has been brought together in an open-source website which is continually updated as new studies become available at open-source website .

As an aid to the interpretation of the evidence base as a basis for determining policy priorities, Place Alliance have developed a place value ‘ladder’ with rungs which climb from aspects of places that should be avoided because they undermine place value to specific aspects which are to be encouraged because they deliver value. For example, amongst those features for which there is strong evidence of positive value are ‘greenness’, mixed use, walkability and public transport connectivity. Features for which there is good evidence of added value include sense of place, street level activity, attractive and comfortable public spaces and integration of place heritage. Features which the evidence indicates have strong negative value include high car dependence, absence of local green space, too many fast-food shops and roads with high traffic volumes.

Benchmarking Place Quality

This very complexity makes the task of assessing place quality all the more difficult, but if relevant policies and priorities are to be determined which can address place quality some way of assessing where a place is currently at - its placeness -is essential. There are tools designed to allow stakeholders to ‘map’ vital elements of a place in a way which embraces not only the physical aspects of a place but also the important social and psychological aspects which contribute to the lived experience within it. Here are two well-known examples.

The Project for Public Spaces (PPS) has developed its ‘Place Diagram’ to help people assess a place. It is built around 4 quadrants of elements focused on access and linkages, sociability, uses and activities and comfort and image, respectively. Each quadrant includes a more detailed listing of aspects of provision relevant to that aspect of place and provides a basis for a conversation about the features of the place in question.

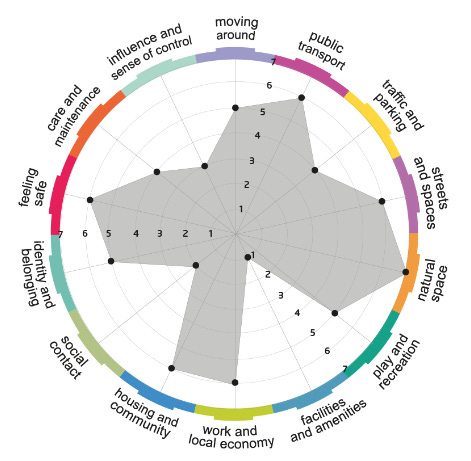

Another example, with a structure that allows clear identification of the strengths and weaknesses in factors which are known to be associated with favorable notions of place, is the Scottish Place Standard tool. Through discussion among stakeholders an agreed assessment on each factor can be reached in a methodical way and represented on a radar diagram such as the one shown. The tool pinpoints the assets of a place across a range of elements which relate to the form, activities and psychological factors identified earlier, and also to those aspects where a place could improve. The strengths and weaknesses amongst these aspects are readily apparent from the diagram.

Other tools are available, often marketed by commercial companies, to provide ratings scales based on particular aspects of place, depending on the interests of their clients. Tools focus, for example, of community values or community ‘liveability’ intended to capture how people rate the lived experience of a place and those aspects which contribute most to that score. Such scales are illustrative of attempts to provide a place profile which can be applied at any level from city to locality, neighbourhood and street based on quantitative and (sometimes) qualitative data and analysis. The reliability and validity of these measures needs to be carefully considered.

Data

The availability of data, especially at small areas levels can be a concern. Many standard government surveys only provide data at local authority level or on electoral ward. The scope of readily available data sets is unlikely to span the range of areas identified in the profiling tools identified earlier. The reliability and validity of data which is available on which to rate specific aspects of place can be problematic, especially on very local areas and on ‘softer’ or more subjective concepts such as sense of place, place identity and belonging, and feelings of safety. There are likely to be significant gaps in data which can limit the analysis of lifestyles within communities and fail to identify groups within communities whose interests may be in conflict.

For a more complete understanding it is vital to look beyond official data sources. Many cities are investing in artificial intelligence technologies which can capture on a wide range of behaviors which can throw new light on lifestyles and activities within a place community and fill some of the gaps through innovative data sources and data linkages. Smart Cities are making rapid and innovative advances in employing ‘big data’ analytic techniques for understanding cities and places within them but there remain issues in interpreting and understanding of the significance of findings for the place community and as a basis for policy response.

Policies for placeness

A prerequisite for policy approaches to place and place meaning, place identity and place attachment is the development of valid and meaningful place profiles derived from processes such as those described here and share analysis with place users and communities. It is vital that the community members are involved in the identification of perceived needs and aspirations and in the assessment of the quality of the lived experience in a place. The more traditional processes of building a community profile used in community work practice should not be displaced by reliance on the use of sophisticated artificial intelligence. Preparing a community profile can often be an iterative process, and pertinent information may only come to light as a profiling process progresses. Information from primary data sources needs to be supplemented by interviews and observations, visits to key locations and from local conversations. Only in this way will the meanings attached to neighbourhoods and public spaces be accessible as a base for future policy actions which capitalize on a place community’s assets, aspirations and build on the its social capital to make place quality and stronger placeness.

Further reading

For more on Place Standard, go to www.placestandard.scot

For more on place value and the ladder of place quality go to www.placealliance.org.uk

Project for Public Spaces (PPS) 2006 – What is placemaking? www.pps.org

Relph E C (1976): Place and Placelessness, Sage publications

Vidal, T et.al (2010): Place attachment, place identity and residential mobility in undergraduate students accessed at (PDF) Place attachment, place identity and residential mobility in undergraduate students | Tomeu Vidal - Academia.edu 23 April 2021