This is a substantial revision and extension of a post on Policies for Places from its early days in January 2023. The couple of years which have elapsed since then have seen a variety of initiatives from grand schemes for levelling-up whole communities to street level placemaking and tactical urbanism. Some concepts like the 15-minute city, placemaking and walkability have come to prominence in urban planning discourse. Impacts of these initiatives have been very variable from the negligible to the game-changing.

And yet cities, towns and neighbourhoods are facing new challenges from extreme weather events, mitigating climate change and reaching net-zero. The impact of the Covid pandemic on patterns of living are still becoming apparent, for example, with the increasing recognition of the importance of green space.

Above all is the need for urban and community resilience in the face of a range of shocks - floods, hurricanes and fires - which challenge the very existence of some places and communities.

So it seems apt to revisit a discussion of the concept of place, of placeness, and place-based policy-making in the face of the emerging context in which cities, towns and neighbourhoods find themselves.

Place-based policy

It is commonplace now for government and local authority policymaking to focus on the centrality of place and ‘place-based’ policy. This is illustrated, by the Scottish Government’s adoption of the ‘Place Principle’ to guide its policymaking and to drive public service reform. The objective of place-based policymaking is not only to aid the development of vibrant successful places in themselves, but also recognizes that it is through places that wider objectives for economic development, sustainable development and social wellbeing will be achieved.

This centrality of place in policymaking raises important questions about how place is understood by public agencies and the extent to which any such understandings are shared between public agencies and by those living and working in place communities. Such understandings are key to how agencies operationalize the concept of place in pursuit of their place objectives, and in turn to how they assess the impact and outcomes from actions for the achievement of their policy objectives. My concern here is to explore the basis on which stakeholders in these processes can judge what is a ‘good place’ and gauge how much progress has been made to achieving such an outcome.

A discussion of the quality of a place is essentially concerned with the relationship between people and their place environment. There are different theoretical approaches in the literature to understanding the people-environment relationship. Following Vidal et. al. (2010), there are 3 central themes: first, places and the process of meaning creation, second identity processes and the relationship with place, and third the bonds or place attachment which people establish with places. Relph (1976) sees place as the outcome of interaction between the physical form of a space, its functionality (activities occurring in a place) and the psychological (emotions, cognitions and meanings associated with a place. He uses the term ‘placeness’ as an overarching term which refers to a state or condition of place which embraces the diverse qualities, interpretations, uses and experience of place. Placeness has various other interpretations but for the purposes of this paper the term will be understood to refer to the ‘quality of being a place’.

Public authorities, planners, developers, employers and residents all have an interest in place quality and the indicators which characterize ‘place’ for them. Policies aiming to build quality places require a multi-faceted approach. They need to seek not only to influence the physical features and layout of a space but also to capitalize on a local community’s assets, inspiration and potential, with the intention of creating places which promote people’s health, happiness and wellbeing, economic security and aspirations for their place and for their community as a whole. Clearly a large range of factors and policy actions will be relevant to the achievement of places which successfully meet these objectives and aspirations.

There is a growing evidence base for linking features of place design with benefits derived by those who live and work in a place. The evidence base indicates that quality design brings added value with respect to health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. The evidence base continues to grow. As a useful aid to the interpretation of the evidence base as a basis for determining policy priorities, Place Alliance have developed a place value ‘ladder’ with rungs which climb from aspects of places that should be avoided because they undermine place value to specific aspects which are to be encouraged because they deliver positive value. For example, amongst those features for which there is strong evidence of positive value are ‘greenness’, mixed use, walkability and public transport connectivity. Features for which there is good evidence of added value include sense of place, street level activity, attractive and comfortable public spaces and integration of place heritage. Features which the evidence indicates have strong negative value include high car dependence, absence of local green space, too many fast-food shops and roads with high traffic volumes.

Benchmarking Place Quality

This very complexity makes the task of assessing place quality all the more difficult, but if relevant policies and priorities are to be determined which can address place quality some way of assessing where a place is currently at - its placeness -is essential. There are tools designed to allow stakeholders to ‘map’ vital elements of a place in a way which embraces not only the physical aspects of a place but also the important social and psychological aspects which contribute to the lived experience within it. Readers will likely be familiar with two well-known examples.

The Project for Public Spaces (PPS) has developed its ‘Place Diagram’ to help people assess a place. It is built around 4 quadrants of elements focused on access and linkages, sociability, uses and activities and comfort and image, respectively. Each quadrant includes a more detailed listing of aspects of provision relevant to that aspect of place and provides a basis for a conversation about the features of the place in question.

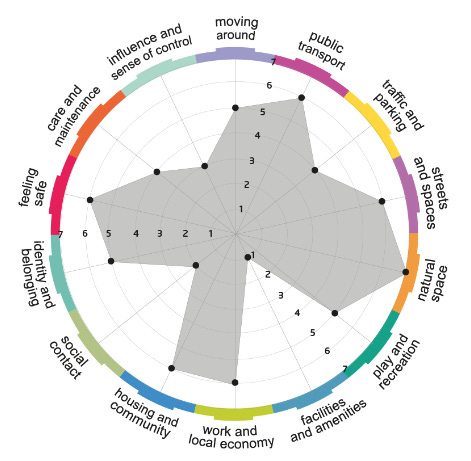

Another example, with a structure that allows clear identification of the strengths and weaknesses in factors which are known to be associated with favorable notions of place, is the Scottish Place Standard tool. Through discussion among stakeholders an agreed assessment on each factor can be reached in a methodical way and represented on a radar diagram such as the one shown. The tool pinpoints the assets of a place across a range of elements which relate to the form, activities and psychological factors identified earlier, and also to those aspects where a place could improve. The strengths and weaknesses amongst these aspects are readily apparent from the diagram.

Other tools are available, often marketed by commercial companies, to provide ratings scales based on particular aspects of place, depending on the interests of their clients. Tools focus, for example, on community values or community ‘livability’, intended to capture how people rate the lived experience of a place and those aspects which contribute most to that score. Such scales are illustrative of attempts to provide a place profile which can be applied at any level from city to locality, neighbourhood and street based on quantitative and (sometimes) qualitative data and analysis. It remains the case that the reliability and validity of these measures needs to be carefully considered with respect to the interests of the user.

Data

The availability of data, especially at small areas levels can be a concern. Many standard government surveys only provide data at local authority level or on electoral wards. In the UK, the smallest area level data is derived from census output areas of around 125 households or 300 people. Although such data can provide a finely grained analysis of the characteristics of areas, the scope of readily available data sets is unlikely to span the range of areas identified in the profiling tools identified earlier. The reliability and validity of data which is available on which to rate specific aspects of place can be problematic, especially on very local areas and on ‘softer’ or more subjective concepts such as sense of place, place identity and belonging, and feelings of safety. There are likely to be significant gaps in data which can limit the analysis of lifestyles within communities and fail to identify groups within communities whose interests may be in conflict.

For a more complete understanding it is vital to look beyond official data sources. Many cities are investing in artificial intelligence technologies which can capture on a wide range of behaviors which can throw new light on lifestyles and activities within a place community and fill some of the gaps through innovative data sources and data linkages. Smart Cities are making rapid and innovative advances in employing ‘big data’ analytic techniques for understanding cities and places within them but there remain issues in interpreting and understanding the significance of findings for the place community and as a basis for policy response.

Planners, developers and placeness

A number of countries, including the UK, the USA and Australia, face a housing crisis arising from the shortfall in the availability of suitable housing at prices that lower and middle-income families can afford. The UK government, for example, has a target to build 1.5 million homes in the next 5 years, and there is a robust debate on where these should be put. First priority is to build on brownfield sites (mostly former industrial land), then so-called ‘grey field’ sites (poor quality land on the edge of towns and cities, and then on greenbelt sites (hitherto protected better quality land around existing towns and villages).

Many of the proposed new developments will be large, 1000 homes and upwards. One gets the impression that a consensus has emerged about what new developments like these should look like. Compare, for example, the descriptions of these major schemes drawn from planning or developers proposals.

A North London council has developed a plan for over 2000 new homes and workplaces in a station growth area south of the town centre. It also has plans for a substantial makeover of the town centre to include a food court, a ‘lighthouse’ pavilion, a permanent street market, pocket forests and more security measures for improved public safety and combat anti-social behaviour.

West Town has been highlighted by the proposed Edinburgh City Plan as an essential part of the vision for west Edinburgh to become a “vibrant, high-density mixed-use extension to the city with a focus on place-making, sustainability, connectivity and biodiversity.” The proposals are to create a mixed-use development as part of a homes-led town centre neighbourhood as well as providing the employment, commercial and community amenity and facilities required for a 20-minute neighbourhood.

Again, Blindwells is a major development on a brownfield site in East Lothian within commuting distance to Edinburgh. When completed it will comprise some 1600 homes and community facilities for health care, a primary school, shopping all set in an environmental infrastructure with wood and green play spaces.

Hind Street village will include up to 1600 homes to transform a large area of abandoned land between two local train stations into a brand new community with new public squares, a park, hotels, gyms, a primary school, health facilities and pubs. The planners say it will reinvigorate this part of the town and bring it back into positive use for the whole community.

Planning for placeness

It would seem place planners and developers have taken on board many of the features of places associated with adding positive value to communities. As well as houses, most plans contain provision for a variety of community resources for public services, shopping, social interaction and green spaces. Some include provision for workplaces and business development. The physical built form may well contain features necessary for the development of new communities and/or extensions to existing communities.

But will the plans lead to enhanced placeness, or risk creating areas of ‘placelessness’?. Planning needs to ensure that large new developments are understood and experienced as places. Continuing actions are necessary to encourage notions of the dimensions of place outlined early in this essay, that is to place and place meaning, place identity and place attachment. The development of valid and meaningful place profiles derived from processes such as those already described here and shared with place users and communities will help. It is vital that the community members are involved in the assessment of the quality of the lived experience as developments proceed and are included in the identification of perceived needs and aspirations going forward if the new developments are to move from merely collections of houses to places in their own right, to the new towns or urban villages to which planners and developers aspire. A place with strong sense of identity and place attachment will be resilient and in a better position to deal with unanticipated issues if and when they arise.

The more traditional processes of building a community profile used in community work practice should not be displaced by reliance on the use of conventional local statistical indicators. Understanding a community profile is an iterative process, and pertinent information may only come to light as profiling processes progress. Information from primary data sources needs to be supplemented by interviews and observations, visits to key locations and from local conversations. Only in this way will the meanings attached to neighbourhoods and public spaces be accessible as a base for future policy actions which capitalize on a place community’s assets and aspirations and build on the its emerging social capital to build place quality and maximize placeness.

Further reading

For more on Place Standard, go to www.placestandard.scot

For more on place value and the ladder of place quality go to www.placealliance.org.uk

Project for Public Spaces (PPS) 2006 – What is placemaking? www.pps.org

Relph E C (1976): Place and Placelessness, Sage publications

Vidal, T et.al (2010): Place attachment, place identity and residential mobility in undergraduate students accessed at (PDF) Place attachment, place identity and residential mobility in undergraduate students | Tomeu Vidal - Academia.edu 23 April 2021