Changing the Rhythm of Life? The 15-minute City and Urban Planning

What is a 15-minute city?

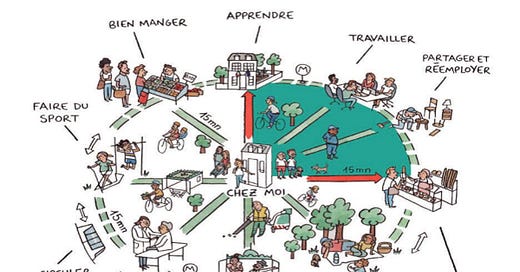

The 15-minute city is an urban planning strategy which is about creating attractive, interesting, safe, walkable environments in which people of all ages and levels of mobility are able to access from home, those day-to-day services and activities they need without using a car. Local services include shopping, education, health, places of work, green spaces and public places for community activities and social contact. This range of places need to be accessible on foot, by cycle or by public transport. The 15-minute city is one consisting of a collection of connected neighborhoods which have these characteristics.

In diagrammatic form, the features of the 15-minute neighborhood are neatly shown below, in an illustration from France.

The Rationale for the 15-minute city

The idea for the 15-minute city can be traced back at least to the Garden City model of development promoted by Ebenezer Howard in the 19th century and given expression in original Garden Cities in England. Despite these early attempts to develop complete, compact, walkable places, especially from the mid-20th century, most cities have nevertheless continued to evolve with distinct separations between industrial, commercial, and residential areas. Whilst this separation meant that many city residents could enjoy cleaner air away from industrial factories and less crowded living conditions, it came with the cost of longer travel times and dependence on the car and public transport for reaching workplaces, commercial and shopping areas, and accessing city services and recreation facilities. Even as cities have evolved further with relocation of industry and blurring of commercial and residential areas, the infrastructure required to support the separation of areas such as major roads and wide streets usually still remains, continuing the dominance of the car in most urban environments.

However, drawing on the ideas of Jane Jacobs and Wilfred H Whyte, and especially following the more recent work of Carlos Moreno working with the City of Paris who coined the term ‘la ville de quart d’heure’, the recognition of the importance of the local area for residents’ quality of life and health and wellbeing has become clearer. An increasing number of cities in Europe, America and elsewhere are now developing initiatives to promote livable neighborhoods as a key part of their urban planning (e.g. Edinburgh, Paris, Melbourne, and Portland Oregon). The adoption of these policies has been given further impetus by the COVID-19 pandemic when restrictions on movement forced many people to live day-to-day within their local neighborhoods.

The narratives which underlie the concept of the 15-minute city can be characterized as:

Environmental

Climate change and greenhouse gas emissions are now priority concerns globally and many cities now pursue zero carbon policies. Encouraging reductions in the use of private cars and the promotion of active travel and public transport are one important response to these concerns and are a major issue for urban planning and development. Eliminating unnecessary traffic from urban areas can significantly reduce a city’s carbon footprint, reduce pollution, and improve air quality.

Health and wellbeing

Poor air quality is associated with many physical and mental health problems such as asthma and other respiratory conditions, heart problems and cancer. As spaces are developed that encourage exercise and more residents take up walking or cycling, health and fitness improves and there can be reduction of conditions such as arthritis. There are mental health benefits which follow from greater opportunities to access green spaces, reduced isolation, and access to support services. Such improvements in community health and wellbeing may be expected to lead to reduced demand for health and community services. Child friendly streets can encourage informal play and increasing independence, both important for child development.

The provision of local health care facilities can improve take-up, and also produce service efficiencies and co-ordination across sectors through the development of community ‘hubs’, or multi-use of public buildings.

Social

Living in more walkable areas can increase social capital through increased social interaction and participation in community activities with others, and the growth of trust within communities. An increased sense of place may lead to increased political activity and community participation.

Areas with more pedestrian traffic have been found to be safer than those with lower walking statistics. More ‘eyes on the street’ aids the prevention of crime, whilst investment in safe streets through the separation of traffic from dedicated pedestrian and cycle ways reduces traffic related injuries.

With streets re-purposed as public spaces, communities can develop sustainable projects such as community gardens, and more outdoor activities and events. Communities that spend more time together outdoors often form closer bonds and demonstrate more social cohesion and greater inclusivity.

Economic

15-minute cities are likely to experience strengthened local economies through keeping jobs and money local. Keeping investment local through community wealth-building can develop the local skill-base and create sustainable well-paid jobs. Businesses can gain from a stronger customer base from local footfall and may be able to offer additional services. Investment in better placemaking can boost land value and property prices as walkable environments become popular places to live and work.

At a personal level residents may enjoy significant savings in the cost of living through reduced car use and increased local active travel. Increased active travel can help minimize unproductive congestion.

Civic

Decentralization of service provision to local neighborhoods represents a significant change from the way many public services are typically delivered and managed. Local government structures too are typically centralized, and policies adopted on a city-wide basis. The localization of services in response to neighborhood characteristics requires a corresponding change towards local decision-making, which is closer to communities. It offers the opportunity for greater community participation and empowerment.

These different narratives indicate many of the expected benefits arising from the substantial change in urban form from a focus on separate single-use zones to a focus on multi-use local areas. Moreno argues this will derive from buildings and streets that mix places for living and working whilst at the same time, reducing time for commuting and unnecessary journeys, and allowing more time for personal interaction and community activities. For Moreno, the objective is not to re-create a village but to create a better urban organization. The 15-minute city relies on a new relationship between citizens and the ‘rhythm of life’ in cities.

Issues and challenges

The 15-minute city idea has its enthusiasts and its critics. Delivering significant change will always attract competing perspectives and raise a range of issues and challenges. Some are highlighted below.

Undermining the soul of the city?

Cities as they have developed through time have been shown to bring many benefits. Agglomeration, (the bringing together of large numbers of people, creating chance encounters and encouraging work specialization and trade that drives the economy) has been demonstrated to be economically effective both in stimulating innovation and in bringing economies of scale. The centralized model of urban development supports the widest variety of opportunity in the labor market and for consumers. It is argued that the necessarily decentralized model of the 15-minute city leads to limited choices, weaker agglomeration and a dampened economy, and thereby undermines the role of the city as it has developed over time.

Nevertheless, those who promote the 15-minute city concept talk of turning cities into ecosystems of 15-minute neighborhoods and can point to economic benefits from urban designs to promote walkability. A recent report from Smart Growth America which benchmarks walkable urbanism across the US claims that although walkable downtowns, town centres and neighborhoods comprise only a small percentage of metropolitan land area they have a substantially disproportional impact on the US economy. Furthermore the study claims that walkable urban places generate a positive impact for the local economy and for local government expenditure.

Who is the 15-minute city for?

Experience with schemes similar to the 15-minute city that already exist suggests that property prices are significantly higher than in car-friendly suburbs, and the businesses that make these compact neighborhoods attractive tend to be niche businesses. Whilst neighborhoods do support pharmacies, food stores and banks, there are often disproportionate numbers of coffee bars, wine bars, boutiques and studios. They can become areas of gentrification. Planning for equity and overcoming more marginalized communities’ suspicions of the approach is a challenge even when the potential benefits to those communities seem clear.

In order to fulfil the notion of 15-minute cities as ‘complete and compact’ a 15-minute neighborhood needs to be diverse, inclusive and offer opportunities to all. The introduction of more walkability, bike lanes and neighborhood parks of itself will be insufficient. The character of its housing provision is likely to be a key factor in securing these objectives. Housing development densities need to be relatively high to support local economic and social activity and service provision. More dense residential development needs to have a range of housing to support a mix of household types, income levels and age groups if the neighborhood is to be properly socially inclusive.

Assessing the Infrastructure deficit?

One of the tasks for planning 15-minute neighborhoods is to identify the key infrastructure requirements within and between neighborhoods, and to improve the infrastructure of under-served areas.

For example, Portland’s strategic plan for a 15-minute city requires 4 key pieces of infrastructure (public primary schools, grocery stores, green parks and public transport stops) to be located close to affordable public housing. Other cities extend this list to include access to a wide range of public services including health and social care, libraries and workplaces. It is likely that it is not only the distribution of community assets which is uneven: often centralized public services may need to be substantially re-configured to achieve sustainable local provision. The infrastructure deficits are likely to vary from neighborhood to neighborhood, but are likely to be most acute in city suburbs where access to most activities is car dependent.

In addition to essential service infrastructure, 15-minute cities need investment in physical infrastructure such as re-allocation of road space, pedestrianized streets, better connected pathways and cycle lanes, street furniture and well-designed public spaces in order to provide walkable neighborhoods, promote active travel and encourage opportunities for meaningful social interaction.

About more than transportation?

Whilst the 15-minute city shifts the focus of city planning from the macro to the possibilities for localization, it is still essential that the dynamics of the metropolitan area as a whole are not neglected. The 15-minute city is intended to be a collection of complete, compact and well-connected places. Many cities have seen the way to start on the route to a 15-minute city approach is to prioritize a focus on improved mobility and public transportation to improve connectivity between neighborhoods and access to public services and community facilities. For many this is being achieved through the imaginative use of road space, the reallocation of parking space from cars to cycles and the creation of car-free or low-emission zones. Some have developed additional cycle and pedestrian only routes between city areas.

There is evidence that these developments can in themselves lead to new patterns of social interaction as significant numbers of people use these different forms of travel and make less use of their cars. This is an important introduction to some of the benefits claimed for the 15-minute city ultimately requires not just better connectivity between existing neighborhoods, but it remains to re-think neighborhoods and neighborhood resources too if its full potential is to be realized. Just as important as convenient transit is the quality of the pedestrian (or cycle) experience. The ability to reach attractive and useful destinations is key to encouraging and keeping people out of their cars.

A policy for real change or just a political slogan?

Whilst some see the momentum behind the 15-minute city concept as driven by media attention or as an unintended consequence of the COVID pandemic, as I have already said there is nothing really new about the idea. New Urbanists have been promoting similar ideas for many years in relation to neighborhood revitalization, the reduction of car use and responding to the pressures of climate change. It is clear though that the experience of the pandemic has been seen by many city administrations as an opportunity to re-model neighborhood development, as they seek ways to respond to emerging changes in working patterns made possible by digital technology during the pandemic and the political and environmental challenges of reaching net-zero targets.

Most agree that cities should become more eco-friendly, and reduce congestion and pollution. However not everyone agrees that more time in community activity and improved local quality of life outweigh the benefits to the economy and consumer choice typically available in current city living. People observe that despite new communication technologies that can allow people to work almost anywhere, big cities maintain their attractiveness for creativity and innovation which comes from large-scale economic and cultural synergies.

Many cities have grown from the absorption of previous smaller places into larger city conurbations, and are taking steps to revitalize local identities and economies. In some such cities, mapping audits show that relatively few areas do not already have access to a basic range of services within a 15-minute travelling time on foot, by bike or public transportation. Arguably the biggest deficits are found in urban edge estates which critically lack 15-minute city infrastructure and are the places where urban design makes it most difficult to deliver.

Systematic evaluations of the impact of the 15-minute city concept are yet to be undertaken. There is growing evidence about the benefits of elements of the 15-minute neighborhood. For example, studies of walkability in neighborhoods show positive benefits on a number of indicators, the importance of access to green spaces on mental health and wellbeing is well established. Writers are noting that living locally has for some overcome the urban isolation experienced by many city dwellers.

So elements of the 15-minute concept are associated with positive changes to social behaviour and interaction. The 15-minute city will be defined by its ability to provide for human needs by walking or cycling for no more than a quarter of an hour, a radical shift from the zonal urban designs of most current cities. The drum beat of the city is changing but the new rhythm is still to be widely felt.

In future essays I will explore the practical steps cities are taking to progress the 15-mnute city concept, and discussion emerging ideas and methodologies for evaluating the impact of such policies.